As Library Company of Philadelphia intern Becca Solnit organizes our material for inclusion in the digital collaborative project Home Before the Leaves Fall: a Great War Centennial Exposition (http://wwionline.org), we in the Print Department have been treated to the largely unexplored visual delights that lurked in our drawers of World War I posters. Posters urging Americans to buy war bonds or not waste food were expected, but posters relating to the war work of the American Library Association (ALA) were more surprising.

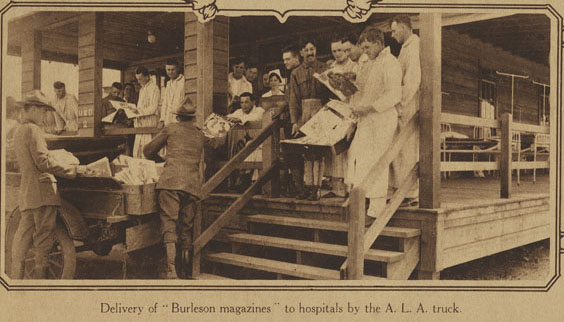

Established in 1917, the ALA’s war time programs, known as the Library War Service, accomplished an impressive number of tasks in a short period of time. While these posters are more utilitarian than eye-catching, the work of the Library War Service was given more visual appeal in posters such as this one urging the public to donate books for servicemen. While this poster encouraged donors to drop off their books at nearby public libraries, another Service initiative facilitated the delivery of magazines to the troops. Created by the Postmaster-General Albert S. Burleson, the special program allowed individuals to mail used magazines for only one cent. This reading material, referred to in publicity as “Burleson magazines” flooded military libraries through the work of the Library War Service. As many as twenty sacks of magazines weighing as much as one hundred pounds each arrived daily at some camp libraries. The group erected thirty six camp libraries with money from the Carnegie fund; raised five million dollars from the public; distributed close to ten million books, magazines, and newspapers to the troops; and provided library materials to over 500 locations, including more than 200 military hospitals. The Library War Service produced a series of posters promoting their work, and the Library Company’s collection includes four from this series. Using a collage of images the posters showed clean-cut soldiers in training camps enjoying library services, wounded soldiers in hospitals receiving books at bedsides, exteriors of libraries on military bases, and the delivery of reading material to the troops stationed overseas. The organization also reproduced many of these images as lantern slides and used them for fundraising presentations around the country.

Even near the end of the war, the Library War Service remained active. Illustrator Dan Smith (1865-1934), who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, created this visually striking poster probably when many soldiers were contemplating their re-entry into civilian life. The books leading out of the European trenches and across the Atlantic to America encompassed practical subjects such as drafting, business, farming, and machine shop work. The Library War Service encouraged soldiers to take advantage of library resources. “Got your eyes glued to some job back home?” read some fundraising material. “Better glue them to the book about it at the CAMP LIBRARY. Stick To It, you’ll get the job.” The Library War Service distributed 100,000 copies of this “Knowledge Wins” poster. The Library Company’s copy was “found in collection,” and it would be great to think that it has possibly been in our possession since its distribution almost 100 years ago.

Sarah J. Weatherwax

Curator of Prints and Photographs

![7066.Q.3: J.P. Widener, Dr. E. La Plos, Marshal Joffre, Viviani [May 9, 1917]](https://projects.library.villanova.edu/wwionline/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/05/7066-q-3-300x235.jpg)